Simultaneous collection of imagery and laserscan data using the Leica Pegasus backpack.

This is part two of a series bringing you up to speed on mapping backpacks. Click here for part one.

Previously, I blogged about what a mapping backpack is and discussed the convergence in technology that has brought this new form factor about. Here we will discuss what types of mapping backpack are available and how we might use them.

Commercial mapping backpacks

Though mapping backpacks have been around for a number of years in the military and university space (as well as at Google), the commercial mapping backpack market is still very small. As of this writing, some systems have only been available for around 6 months and so I think it is fair so say that we (both vendors and customers) are still learning about their capabilities and possibilities. Due to these limitations, the following is not intended to compare systems, but to provide a high-level overview of what is available based upon publicly available materials.

The systems available have been loosely grouped based upon whether they are ‘measurement systems’, where the user can obtain 3D measurements directly from the exported data without further processing; and ‘image-only’ systems where the exported data consists of an image log.

Measurement systems

Since mid-2015 we have seen two global players marketing mapping backpacks to the professional survey and geospatial imaging industry. Microsoft offers the Ultracam Panther and Leica Geosystems offers the Pegasus: Backpack. Here’s a quick rundown of their specs:

Sensor

Both systems take advantage of the recent miniaturization of sensors by including the Velodyne VLP-16 ‘Puck’ LiDAR.

Camera

— Microsoft’s backpack, drawing upon the company’s experiences in producing camera systems, also wields a 68 megapixel spherical image capture system that is marketed as providing the highest resolution data available.

— Leica’s backpack utilizes five cameras strategically placed to provide a 360° x 200° field of view.

Positioning

Both are equipped with full inertial navigation (INS) rather than a GPS-only positioning system. This means that these mapping backpacks collect camera imaging and LiDAR data simultaneously. It also means that they provide a means to automatically reference the spatial location of data collected both in outdoor and GPS-denied environments.

When GPS is not available

— Microsoft’s backpack optimizes its position information using their visual odometry sensor.

— Leica’s backpack uses positioning strategies based on simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM).

Mapping backpacks such as the Pegasus and the Panther provide a means to measure the data captured.

Imaging-Only Systems

In considering application scenarios of mapping backpacks it is also important to consider systems that provide only imaging. I have already mentioned the Google Trekker for capturing immersive imagery for Streetview.

Mapping inaccessible mountain routes using Spherevision 360 systems and software

Another system (also not new) is Arithmetica’s Spherevision Portable360 camera system. Though it has been commercially available for over five years, the Portable360 is still considered to be the only system that provides a real-time immersive view of the environment. While the system is not equipped with a full INS, the images taken as the user walks can either be georeferenced via GPS waypoints or manually positioned against a floorplan within the accompanying software, Spherevision RouteView 360.

Why use an image-only system? In the context of disaster response or hazard mapping on large industrial sites or military facilities, an immersive image-based view is what is required—and nothing more.

Will backpack mapping replace current procedures?

Typically, when we look to implement technologies it is to make an existing process faster and/or cheaper. Mapping backpacks have the potential to reduce the time and manpower required on-site. In the context of capturing survey data for use in facilities management, a backpack could lead to a reduction of time on-site, from one day of laser scanning for a two-person crew to perhaps one hour on-site for one person. Is the data collected going to be useful though?

Let’s consider a specific application: scanning building interiors for facilities management. The conventional approach would be to use a static, terrestrial scanning workflow. This will provide accuracies of <10mm.

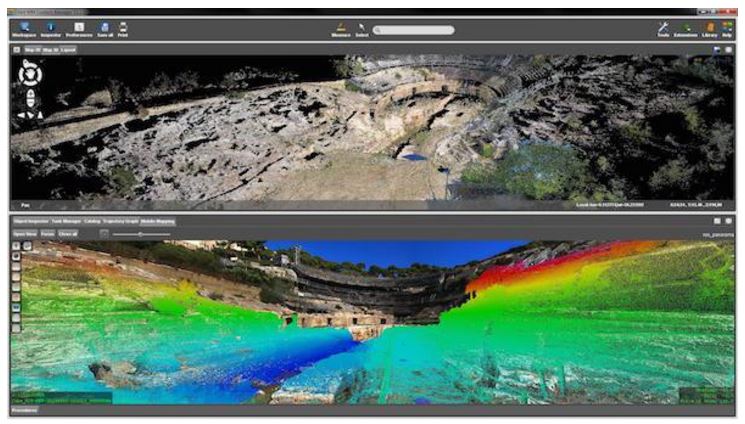

Ultracam Panther imaging and lidar data visualized in Orbit GT

The Panther or Pegasus (as a function of the types of sensors that they use) will provide data that typically falls within a relative accuracy budget of +/- 20-30mm. In addition, we must account for the absolute positioning capabilities of the backpack, which can range from 5cm-50cm. We must also consider the survey control necessary to tighten these.

While this is an application that many of us would want to use a mapping backpack for, is it really where we will obtain most value?

Seeking new applications and being fit-for-purpose

When the Pegasus was launched, I read with interest a discussion on the Laser Scanning Forum. Some posts suggested that a mapping backpack of any kind was a suspect idea, since you can’t collect data that you could measure to the project specification. However, I liked the suggestion that we should be seeking new applications for these technologies. Rather than using the backpack for building dimensioning, it was suggested that perhaps we should be thinking about collecting data for ‘pipe trenches’ or overhead ‘pipe racks’ where a 50mm tolerance can be good enough.

In other words, might the backpack shine for data collection in otherwise restricted environments?

Conclusion – why are you collecting the data anyway?

Given the plethora of highly accurate imaging systems that we now have available (for example, reasonable priced terrestrial scanners), how about we use those for applications where accuracy is important, and continue to look for applications for backpacks where being fast and realistic are our greatest concerns?

How about:

- Concentrating on the value of collecting data along difficult to access routes? For example, tight corridors, mines, cross-country pipelines…

- Rather than being focused on measurement in asset management or a construction build; we see the value of a mobile backpack in being able to quickly collect immersive imagery of a site build that can be used to unify construction teams during morning site meetings?

- We focus on the data management practices associated with managing data from multiple backpack data collects for actionable projects such as site condition monitoring?

- Concentrating on the value of collecting data along difficult to access routes? For example, tight corridors, mines, cross-country pipelines…

These are all applications that are possible now. Maybe we should focus the development on easy-to-use and cost effective systems accordingly.